everybody’s a critic

or, maybe anybody can be

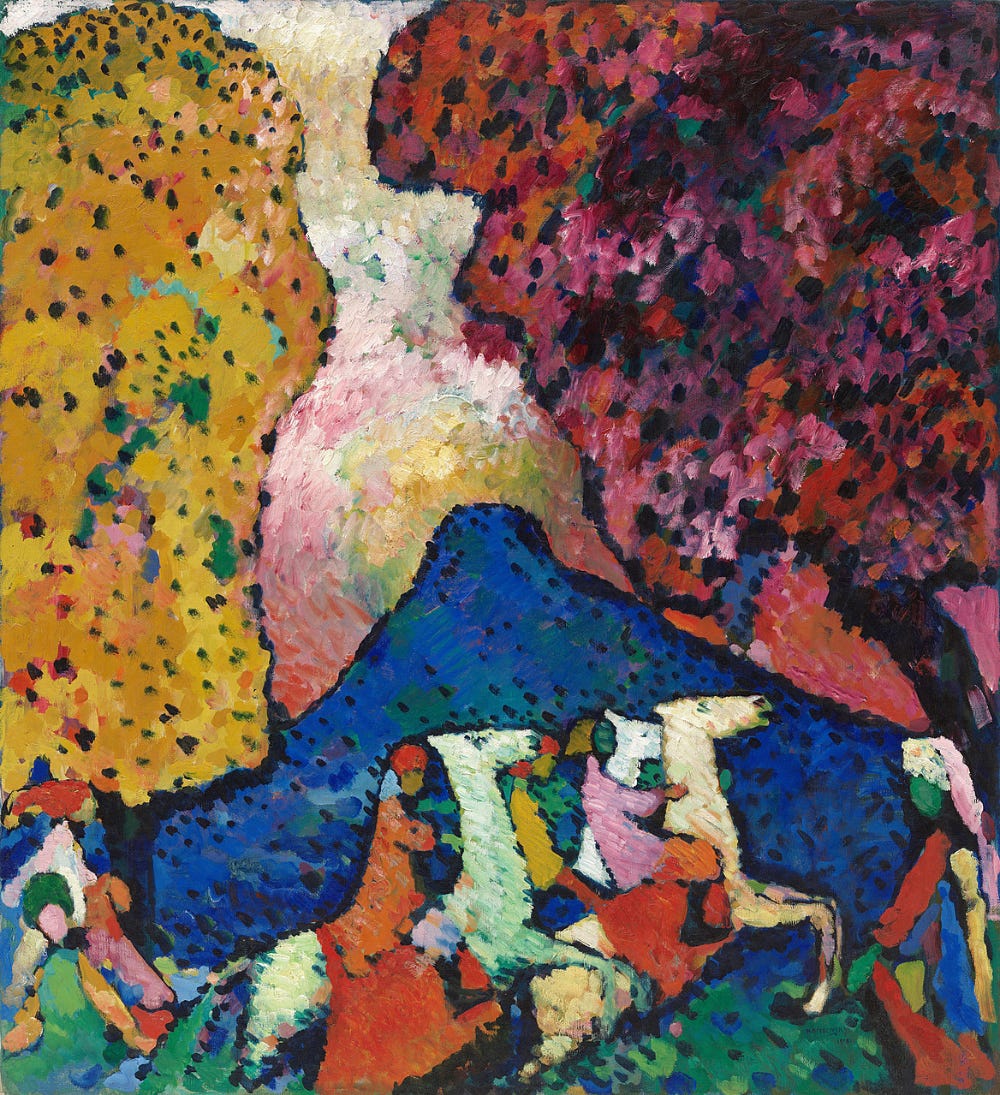

You don’t really know what you’re looking at first. Blocks of color divide up the canvas into four, maybe five sections, your eye starting at the glimmering center of the work: a mix of pinks and whites, yellows and greens delicately made up of individual daubs of paint that seem blend together into a glowing mass. Then, the rest of the image draws you in, between the golden tree speckled with green leaves, the contrasting reddish mass of another tree, and the deep blue mountain from which the painting gets its name. Finally, the horse riders appear, physically taking up a third of the image, yet unseen in contrast to the rest of the work.

I can tell you all that the painting is Vasily Kandinsky’s Blue Mountain. But this is where my abilities fail — I can tell you I spotted the painting across the room in the Guggenheim and was drawn to it, that I was brought to the verge of tears when I approached it, but I can’t explain why. I can’t point to the successes of the work and why it makes me feel so much, why it’s such an important work of art. Despite all of my years of writing, I can only show you so much.

The gap here is between me and the work of successful critics, that often maligned group that seeks to illuminate the experience of film, literature, culture, anything. The role of these writers is to express an opinion about these works and prove that this opinion is worth sharing at all. The best of these critics employ a rich knowledge of the genre or the medium, even the process behind how the works came to be. And there’s the way New Yorker theatre critic Vinson Cunningham describes criticism: an attempt to stop the horizontal continuation of time and assert one’s love for an experience by erecting a monument to it. The work of criticism can be to care so much about an experience that you must do everything you can to make the moment legible to another.

It’s easy to see reviews as value judgments on subjective matters, and they are, but they also act as ways of orienting on how a medium can be understood. How did I learn to understand the art forms that I can talk about with some level of confidence? With film and literature, courses in high school and college enlightened me about what a given work could do. These courses were built on film and literary criticism, dissecting individual movies and books piece by piece to show how the use of language or mise en scène of a film could capture an audience for generations, become beloved over and over again. And this work turned an enormous corpus of art into something consumable, understandable.

Because of this education, because of the work of previous critics, when I talk about a film or a book, it feels like I can start to explain what moves me about it. Armed with a vocabulary about the work, I can identify how the shot selection puts you in the shoes of the protagonists of The Seventh Seal (1957), how the individual characters have their stories built up to a conclusion that makes the whole film shine so brightly, how all of the pieces working together still haunt me months after watching it.

With music, my taste has been shaped for years by the critics at Pitchfork, who dispense in-depth reviews that highlight both what an album does, and what an album could be. I’ve listened to Carrie & Lowell hundreds of times, but Brandon Stosuy’s review gives me the vocabulary to explain why, ties the threads to Sufjan’s previous albums, and lets me parrot it out whenever someone asks me why I adore it so much.

But when a friend asks me what makes Blue Mountain so good, I must admit that I can only rely on my aesthetic experience of the work — how it made me feel so much. My education here is incomplete; I’ve read too little art criticism to be a critic, I know too little to share my opinion in a useful manner.

I feel so constrained by this. I was once a person who felt nothing, I once felt so much worse, I once was shy and small and sad and empty. And then I became less so, through many things, but through living beautiful experiences (awful and awesome) and swallowing all types and forms of art (awesome and awful). What am I supposed to do when I want to share the transcendent things that changed me?

I can wax poetic about my feelings, find the most magical combination of words to describe teardrops, but does that come close to letting you into the experience? Even as I build a monument to an experience, what does it accomplish if the work stays opaque to someone unfamiliar with it? As I deepen my relationship with visual art, with any other medium that I don’t currently understand well enough to explain my love, I wonder how I can move closer to what these critics do, to build better monuments.

Maybe it’s my fate. In middle school, one of my classmates told me that I should be a critic when I grow up, probably due to my tendency to point out the shortcomings of nearly everything I encountered. It was intended as a slight, underscoring my perceived negativity towards music that he shared with me or ideas he had about the world (whatever ideas a couple of 12-year-olds could muster), but even with my limited understanding of what critics did, I didn’t see what was wrong with being one. I loved the idea of being so confident and cogent in my opinions that other people would take them seriously enough to publish them.

Part of my admiration for getting to that level is that everything takes so much time; there are lifetimes of learning for everything under the sun. Someone somewhere has spent years discovering the most perfect buttons in the world for their shirts, and I only notice them when they stop working as intended. Learning deeply about any subject, from fashion to dance to anything else, sheds light on potential. When you understand the process that goes into creating something, when you can see a painting or a musical or a song for all that it is in full glory, you remember that there are truly tremendous things possible in the world, capable of shaking anyone to their core. And in each work that you encounter, you’re able to see where the potential is achieved, where things almost did, and to show everyone else what your knowledge lets you see.

Pondering all of this, I desire to learn enough to resemble a competent critic, and I return to another quote from Vinson Cunningham, “Anybody can be a critic. All it takes is curiosity, and the willingness to share your observations with others.” Hearing this, I’m confident I can be.

💧 Drops of the Week 💧

ALBUM - Disintegration by The Cure - extremely late to The Cure, but they’re good!

POEM - “Meeting the Light Completely” by Jane Hirshfield - Even the long-beloved / was once / an unrecognized stranger.

the best feelings are preverbal tho