the cave painters

and the modern writer

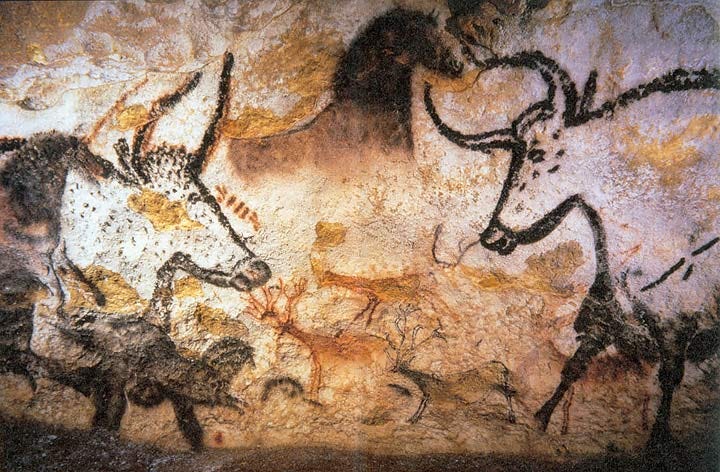

One day in 1940 in Nazi-occupied France, four teenagers and a dog stumbled upon a cave beneath an uprooted tree. Deep into a war ravaging the entire world, as men attempted to assert their will and their importance across Europe, these boys gazed, awestruck, at walls that would've astounded their ancestors millennia before. Within this cave, they traveled back in time, discovering walls covered with hundreds of paintings dating back over 17,000 years.

The many paintings in the Lascaux caves are thought to have been painted by many different generations of early man. Each generation would learn from the existing paintings, and create their own versions, sometimes overlapping. It was art school, it was intergenerational learning, it was a religious space. In the flicker of firelight, the images seemed to come alive and move.

There were very few images of man on these walls. No, like the Paleolithic world, the caves were filled with megafauna, some still extant, some long gone — bulls & equines, aurochs & stags, a single bear. Those days, it wasn't a man's world. Man was something small compared to the apex predators and the enormous herbivores, and man was humble enough to honor these beasts with their paint.

We don't know a lot about the time before writing. We don't know why these paintings were created, what they might've meant, who would've held the brush, and what a painter would've gotten out of the experience. In a world that was likely filled with greater amounts of death and loss, hardship and toil, humans still found a reason to make art. And somehow, this art survived thousands and thousands of years, awaiting the day that a tree would fall, and some kids would uncover the splendor once more.

I think about Lascaux all the time — how incredible it is that it exists at all, how two of the boys served as guides for the cave for most of their lives, how certain paintings exhibited forms of perspective that didn't reappear in art until the Renaissance. It feels like proof that there's an inherent human need to create art, despite the circumstances.

These ancient artists have been haunting my thoughts more than usual lately, as I've been trying to counteract my waning motivation to write over the past few months. It increasingly has been feeling like I'm simply releasing words into a river of content, reaching fewer people than ever before. Maybe there have been other times in history where more art has been made but it has never been done so visibly. In this version of the world I can hardly keep up with the work of my friends these days; I'm sure my friends feel the same way. As I tried to find the point of feeding into the endless stream, I tried to put myself in the shoes of our ancestors.

Any given post of mine probably reaches more people than any of these painters would ever meet in their lifetime, and here I am, feeling disconnected from my work. But, even though we can't possibly know the motivations of the Lascaux painters, I imagine that the painters didn't care too much about how many people saw their work, that they could lose themselves in the craft as an escape from the dynamic world around them.

Obviously, the world has changed enormously, yet re-focusing on the process of creation feels like an evergreen lesson. I've even learned this lesson before. A few years ago, I wrote a piece for a magazine that argued that the only way to sustainably create any sort of art was to fall in love with the process, rather than fixating on the result and the response.

Even though I was happy with the piece when it came out, I was forced to practice what I preached: the magazine folded within a year of publishing. The contrast with Lascaux is laughable — their paintings outlasted entire civilizations, my essay barely lasted the lifespan of a rat. This was the sort of randomness that the results that a given work of art could entail. This randomness was no place to build the foundation of an artistic practice.

So I return to thinking about the process, about craft in all forms. My state of artistic ennui led me back to trying to learn how to draw again, my fourth or fifth attempt at the practice. Watching tutorials and reading books about the practice are always torturous — the teachers seem otherworldly in their abilities to draw straight lines, render perspective accurately, make an image appear out of nowhere. Their skill comes from their repeated effort at their chosen craft, despite the results, or lack of results.

And this is true for any craft, including writing. I notice it as I try to help my father write a eulogy for his late friend, or consult my cousin about his college application essay. After writing 357 of these newsletters along with several other pieces and poems, I had forgotten about the progress that I've made, about the way my mind transformed. I had forgotten that it didn't always come so easy to bring disparate ideas together into a coherent narrative, that even my worst essays these days blow my 2017 essays out of the water. I had forgotten that art can be a process of self-transformation, with the side effect of a pile of work.

Returning again to the photos of the cave walls, I remember when I first saw these images in an art history class over a decade ago. They didn't seem very special to me then, before I'd ever begun any sort of artistic journey. Then, they were just some marks by some cavemen, but now, they feel like the marks of a fellow artist, someone who may have faced struggles and triumphs in their practice just as I have. All that is left is what Picasso said, after witnessing Paleolithic art for the first time, "we have learned nothing in twelve thousand years."

💧 Drops of the Week 💧

ARTICLE - “‘Humans were not centre stage’: how ancient cave art puts us in our place” by Barbara Ehrenreich - the piece that informed a lot of the details about these caves!

POEM - “The Peace of Wild Things” by Wendell Berry - I go and lie down where the wood drake / rests in his beauty on the water, and the great heron feeds.